Scented candles are pleasant at home or the office, and easy to acquire. They brighten a room, filling it with pleasant scents that soothe our senses. During our ancestor’s time, candles were hand crafted necessities, made with only what nature provided. A successful hunt, tallow and a wick summed up the Appalachian art of candle making.

Appalachian Candles Begin at the Hunt

Winters are harsh on the mountain, so preparations start in August. Wax and wicks are needed for warmth and light. A candle in the windows acted as a beacon home. A small family could use an average of 160 to 200 candles during the colder months. Tallow must be rendered and cotton is needed for wicks.

A good candle starts with a successful hunt. The game provided fat used for making tallow. Beef was favored, but on the mountain, possum, turkey, groundhog, wild boar, or deer were more likely sources. Each produced a different grade of tallow, with boar being the least desirable. It is said to produce a rancid smell with black, oily smoke. Deer, turkey and groundhog will burn cleaner.

By FotoosvanRobin – originally posted to Flickr as Niervet in potje met zout en peperkorrels, CC BY-SA 2.0

Tallow Time

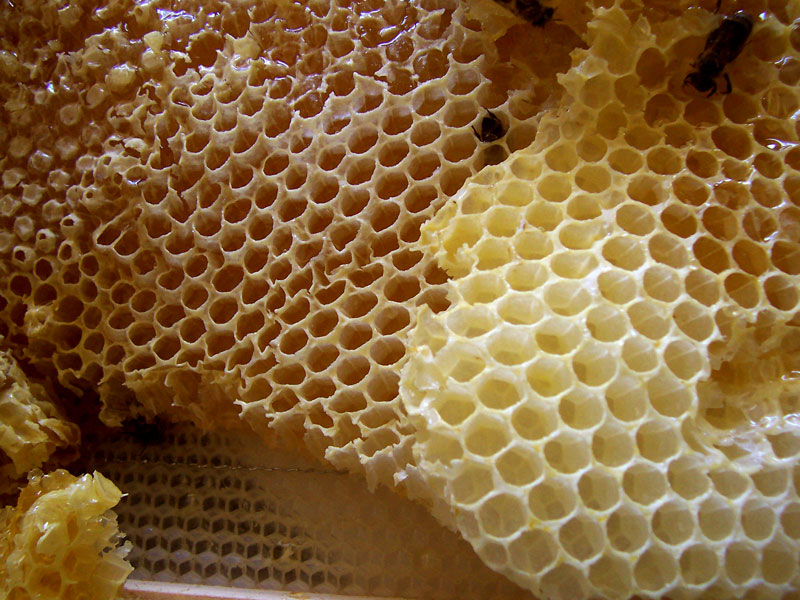

Tallow is rendered by mashing and stirring fat into a liquid. This process cannot be done quickly. Slow cooking at a lower temperature creates a thicker base with less loss. A 10 pound batch of fat can render anywhere between 5 to 8.5 pounds of tallow. The type of animal and skill of the cook created the variable. Bee wax would be mixed in when available. If ¼ of the wax mix was bee wax, the candle burns more slowly, giving off a pleasant scent.

Bayberries were sometimes used because of their wax like coating. If used alone, their wax did not last long. If mixed with tallow, they gave off a pleasant smell. Some skilled candle makers would add scents via pine, cedar, berries, or nuts to batches of tallow for special occasions.

Wick Dip or Mold

The wick was as important as the tallow. Strips of cotton were tightly twisted in order to form a wick. The tighter the twist, the better it would burn. The strips of wound cloth were dipped into vats of tallow, held a moment, and lifted out. This is repeated 15 to 30 times, depending on candle size. Multiple wicks could be tied to a broom or stick, then dipped simultaneously. When working together, a family could dip enough candles to last the winter in 48 hours.

Some Appalachian candle makers preferred cast iron molds. The wick was placed in the mold and filled with tallow. The set, pour and wait method was much easier then dipping. However, one could only make as many candles as they had molds. Often times, dipping and molds were used in unison.

Modern Candle Artisans

Homemade candles have been gaining popularity. One sniff of a well made candle can inspire feelings of happiness and relaxation. The art of candle making has grown more popular with tallow, paraffin, beeswax and soy bases available online. The hunt became obsolete, allowing a modern artisan to easily create aromatic wax works of art. Premade oils make aroma simple. Still, some Appalachian candle makers enjoy blending real flowers, trees and herbs for a more original or personal scent.

To me, a favored candle provides warmth and ambiance. Plus, they come in handy if the power goes out. Our family tends to keep an ever growing reserve. A renewed love of the Appalachian art of candle making is taking root. If you are looking to invest in homemade candles or supplies, check online, at the local farmer’s market, flea markets, or farm and garden events.

May your candles burn long and bright!

J Shockley

**Reference

http://www.carolinacorner.com/attractions/historical-stories-surviving-appalachian-winter.htm

https://pioneerthinking.com/candle-making-in-colonial-america